In this final chapter of The Fold, Deleuze argues that Leibniz has a specifically musical conception of a pre-established harmony. Up to this point, we have treated the harmony between the monad and the world or the body and the soul in a primarily visual way. The harmony between these terms was simply a result of the fact that they are two sides of the same curve, whose shapes thus naturally fit together. But we know there must be more to this concept of harmony than this rather trivial observation. For Leibniz, this is not just any curve, but the infinitely folded curved of the best possible world. On one side, a single unified and continuous world is actualized in the infinity of distinct monads. On the other side, it is realized in the infinite machinery of organic matter, where each organism unifies and organizes others ad infinitum. So there is not merely a harmony between matter and soul, but a harmony within each side. For Deleuze, this particular conception of harmony is tied directly to the Baroque art and music of Lebiniz's day, and gives philosophical expression to the world which invented opera as the total artwork and developed music from melodic monophony and polyphony towards the use of chords. I won't try to dig into all the details of the musicological or art historical correspondences that Deleuze mentions. Instead, I'll just focus on understanding the two aspects of musical harmony that Deleuze focuses on -- spontaneity and "concertation". Each monad spontaneously sings the whole world independently of the others, expressing its full harmony with a progression of chords drawn entirely from within. And yet, somehow all these monads manage to sing the same world together, so that the play of their chords doesn't clash except as means to a higher resolution. The best world harmoniously unifies the maximum variety.

But how does this harmony work in detail? What makes the type of unity in variety it implies specifically musical? Deleuze's answer is to rebrand the concept of "hallucinatory perception" we saw back in chapter 7 as a form of music -- each conscious perception is an accord between a certain set of differential variations or micro-perceptions. Here, it's helpful to note that "accord" is the French word for a musical chord. This rebranding might remain at the level of word play if it weren't for two factors.

First, this model of perception as fundamentally hallucinatory rather than representational actually helps us understand why perception feels the way it does, or more precisely, why it feels any way at all. In this scheme there is no objective or neutral perception (or at least perception doesn't begin here). Instead, every perception automatically means something because it is referred to the changing internal states of the organism that has it. In short, every perception has vedana, or "hedonic tone" in a direct way. Just like every musical chord. We can't listen to major and minor chords without seeing heroes and villains, nor hear a dominant seventh without demanding resolution. These mere confluences of frequencies have immediate emotion and direction and give music its special place as, " ... both the intellectual love of an order and a supra-sensible measure, and the sensible pleasure derived from bodily vibrations." (F, 177).

Second, Deleuze shows us in detail how Leibniz's conception of harmony was based on series of inverse numbers like the harmonic series, and the harmonic triangle which he invented. In fact, we can see the monad itself as an inverse number, the reciprocal of God.

According to Leibniz, the monad is indeed the most "simple" number, that is, the inverse number, the reciprocal number, the harmonic number: it is the mirror of the world because it is the inverse image of God, the inverse number of infinity, 1/∞ in place of ∞/1 (just as sufficient reason is the inverse of infinite identity). (F, 179)

The monad is like the infinitesimals of non-standard analysis -- there's a whole world packed into this number which is smaller than the smallest 1/n. But while each monad includes this infinite world in its denominator, it does it from a certain point of view. The infinitesimals are all distinct, and we can think of each as centered on the point of view of a particular n. That is, even though every monad is 1/∞ a given monad is also 1/n for some value of n. This n constitutes the domain of clear perceptions or neighborhood of the monad, which Deleuze has already shown us is composed of a series differentials that enter into relations.

Each monad includes the world as an infinite series of infinitely smalls, but it can constitute differential relations and integrations only on a limited portion of the series, so that the monads themselves enter into an infinite series of inverse numbers. Each monad, in its portion of the world or its clear zone, thus presents chords [accords], insofar as what is called an "chord" is the relation of a state with its differentials, that is, with the differential relations between infinitely small units that are integrated into this state. Hence the double aspect of the accord, insofar as it is the product of an intelligible calculus in a sensible state. To hear the noise of the sea is to strike a chord [accord], and each monad is distinguished intrinsically by its chords: monads are inverse numbers, and the chords are their "internal actions." (F, 180)

So now we can see how the perceptions of a monad are 'musical'. Each perception is like a set of overtones in the harmonic series which come together into a particular chord. This is exactly how the harmonic triangle is defined: 1/6 = 1/2 - 1/3 or in musical terms, the G an octave above will harmonize with both the C and G an octave below. And in fact, the triangle provides for the expansion of each of its unit fractions into an infinite series of other fractions. Every tone is broken down into an infinite sum of overtones. Each monad contains all the rest, but ordered in a particular fashion according to its point of view. Naturally, this point of view changes as the curve of the world varies, so that the infinite series of differential relations that enter into the momentary state of the monad are constantly shifting. The life of a monad is this passage from one chord to another, from the major to the minor and back, and even occasionally all the way to complete dissonance. Each of these perceptions is both the solution to a set of differential equations and a felt reality. Monadic experience is inherently musical, it's existence an unfolding progression of internal chords.

There literally a musical harmony at work within each monad, a kind of spontaneous song or chord progression (F, 182). But this spontaneity does not prevent the monads from all expressing the same world together as a harmony between them. Though the monads are completely separate and never hear one another's song, they nevertheless harmonize perfectly in what Deleuze calls a "concertation". But how can this almost telepathic coordination happen? Here, Deleuze provides what I think is a really ingenious answer that implicitly accounts for the arrow of time. In a way, Leibniz's world can sometimes seem strangely static, or perhaps more accurately transtemporal. The entire history of a monad, everything that will happen to it and every interaction it will have is included within it all at once. We've spoken of a chord "progression", but in fact the entire score that includes all these perceptions as predicates is there at the beginning. So why exactly is there any such thing as time in this world?

The answer has to do with shifting relative distributions of clarity and obscurity which correspond to chords shifting from resolution to dissolution. Since the monads all interlock as expressions of a single world, a clear region in one monad corresponds to an obscure region in another. In fact, we've already seen that the necessarily obscure regions in each monad correspond to the shadows of the other monads (F, 110). This was actually the root of the organic body that every monad must have, a body which folds together or folds up an infinity of obscure parts that remain hidden from us in order to open up our clear zone of conscious perception. In short, there is an order to the way the monads express the same world; they don't all sing the same song in unison. This is the order we call "causality", a concept which inherently involves time.

There is thus a kind of law of the inverse [loi des inverses]: there is at least one monad that expresses clearly what other monads express obscurely. Since all the monads express the same world, it would seem that a monad that expresses an event clearly is a cause, while a monad that expresses it obscurely is an effect: the causality of one monad upon another is a purely "ideal" causality, without real action, since what each of the two monads is expressing refers solely to its own spontaneity. However, this law of the inverse would have to be less vague, and would have to be established between monads that are better determined. If it is true that each monad is defined by a clear and distinguished zone, this zone is not immutable, but has a tendency to vary for each monad, that is, to increase or diminish according to the moment: at each moment, the privileged zone presents spatial vectors and temporal tensors of augmentation or diminution. A single event can thus be expressed clearly by two monads, but the difference nonetheless subsists at every moment, for the first expresses the event more clearly or less confusedly than the second, following a vector of augmentation, while the second expresses it following a vector of diminution. (F, 183)

While we may not be able to isolate a single monad as the absolutely clearest expression of a given event, there is still an order of relative clarity as judged by standards internal to each monad. The clear zone of each monad is constantly growing or shrinking following the major and minor chord progressions we discussed earlier. And the relative clarity of each monad's expression of a given event depends on the direction, so to speak, from which it itself enters into that event (and vice versa). This relative scale is immanent to each monad and yet also establishes a hierarchy amongst all the monads at every moment. This is effectively an ordering of time, which moves from more clarity to less clarity across monads.

Causality always goes, not only from the clear to the obscure, but from the more-clear to the less-clear or the more-confused. It goes from what is more stable to what is less stable. Such is the requirement [exigence] of sufficient reason: the clear expression is what augments in the cause, but also what diminishes in the effect. (F, 184)

Every monad folds up the same infinite world, but they differ each moment in how tightly they 'pack' it, on how much can be included in their clear zone. Concertation is the guarantee that there is a harmony amongst monads such that when one folds into a tighter shape, another unfolds into looser configuration. This doesn't occur because of an interaction between them, but because of a pre-established harmony, where the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle always fit snugly even though each is changing shape at every moment. Or to use the musical analogy, there is an "accord between accords" (F, 183) or a, "correspondence according to which there can be no major and perfect chord [accord] in a monad unless there is a minor or dissonant accord in another, and inversely" (F, 185). It's almost as if there's a total quantity of clarity available in the world (F, 185). The image is of a 'clarity wave' which propagates through the world, expressing itself in the movement of each monad. In the wave, we can see both aspects of harmony -- when we look closely, there is no wave, it is 'nothing but' individual particles of moving water; and yet who would deny the reality of the tsunami produced when the movement of all these particles align.

It may at first seem like a stretch to associate this harmony across monads with causality, because we typically have such a linear billiard-ball notion of that concept. How can there be causality without interaction -- ideal causality? One way to approach this is through the 'logical' causality of sufficient reason. We usually say a theorem about the properties of the triangle "follows from" rather than "is caused by" its definition. But the point is similar in either case -- there is an order of deduction from what it clearest to what is most obscure and surprising. This is precisely the problem sufficient reason is meant to address. It posits that even the most obscure and accidental things which happen to us follow from our definition or essence. They merely unfold what was folded up in this idea from the beginning. This same logical order of unfolding must also apply to the collection of monads which together compose the best world. Everything that happens to a monad, even the dramatic shrinking of its clear zone in death, happens for a reason and fits into the larger plan deduced from the condition of the best.

Spontaneity is sufficient or internal reason applied to monads. And concertation is this same reason applied to the spatio-temporal relations that flow from the monads: if space-time is not an empty milieu, but the order of the coexistence and succession of the monads themselves, the order has to be directed, oriented, vectorized [fléché, orienté, vectorisé]; and in each case, we go from the relatively more-clear monad to the relatively less-clear monad, or from the more perfect accord to the less perfect accord—for the most-clear or the most perfect is reason itself. (F, 185)

Another way to think of the connection between clarity and causality would be by analogy to the second law of thermodynamics. The time variable in the laws of classical physics is completely reversible, which makes a mystery of why it always seems to flow in one direction. If we think of the statistics of a situation though, we see that for every one ordered state there are many possible disordered or partially ordered states. The concentrated drop of ink diffuses in the glass of water. Time moves from singular clarity to manifold obscurity, from order to disorder. In a sense then, this time doesn't depend on any interactions between particles, but simply on the statistics of the possible worlds of their independent configuration. The arrow of time requires a concept of order, a spiritual concept that exists in a different dimension, so to speak, from natural law.

But both these interpretations are merely sketchy initial thoughts. The question of time and causality here seems extremely complicated. For starters, its seems at first as if each monad should have an independent time of its own, governed by the expansion and contraction of its clear region. After all, we have talked about a "progression" of internal chords. In another sense though, since this all happens internally to the monad, it doesn't really happen in time -- the monad is fundamentally a trans-temporal entity. Time seems to arise only at the level of the world, the level at which we can say that there is an interaction -- even if an "ideal" interaction -- between monads. And yet, this world is included within every monad, so we end up going in circles here. Is time objective or subjective? Mu.

------------

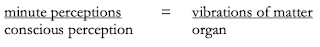

While Deleuze ends the book with this idea that the harmony of the fold is specifically musical, I'd like to close by backing up and restating the concept in more general philosophical terms, in the hopes that this will help me recognize it everywhere I find it. One way to do this is to explore a diagram that is curiously absent from Smith's draft, but should appear on page 176.

The context for this simple diagram is Deleuze's discussion of the three elements of Baroque allegory: "... images or figurations, inscriptions or maxims [sentences], and personal signatures [possesseurs] or proper names. Seeing, reading, dedicating (or signing)." (F, 174). We can think of these elements as arrayed in a cone -- images are spread throughout the base, but are increasingly joined together with inscriptions or propositions that gradually rise up to a summit or personal point of view that includes all these propositions, as well as all the figures they apply to, from a single perspective. The image Deleuze has in mind here is the painting within a painting in the frontispice of Emanuele Tesauro's The Aristotelian Telescope a treatise on Baroque art.

The crucial thing to understand here is that the point of a cone is not the same thing as the center of a circle -- the unification it provides to its figure is different because it involves a different dimension than the things it unifies. In this sense, the unity of the cone is only a projective one, and this is why we see the anamorphosis of the phrase "Omnis in unum". The letters of the phrase are scattered about the base of the cone and don't necessarily seem to relate to one another. But as we ascend the cone, the phrase becomes legible, until we reach the summit and occupy the point of view of the painter herself. From there we can directly read this proposition off of the world. It has merely been projected onto the base in a fashion which distorts it from every other angle. In short, the point of view is another dimension we can occupy to see the unity in the world.

... the transformation of the sensible object into a series of figures or aspects subject to a law of continuity; the assignation of events that correspond to these figured aspects, and which are inscribed in propositions; the predication of these propositions to an individual subject that contains their concept, and is defined as an apex or point of view, a principle of indiscernibles assuring the interiority of the concept and the individual. This is what Leibniz sometimes summarizes in the triad "scenographies–definitions–points of view." (F, 176) (also see the important footnote 263 to this passage)

The point of view is the spot from which the world makes sense, the place that includes all the true propositions about it. This is distinct from any abstract concept of the world that would serve as central point or least common denominator or most universal thing because the point of view of the cone unifies the picture without losing any of its details. All the images of the base are preserved by being folded into the summit of the cone, and they can be restored by a projection from this point. This is what's unique about the peculiar unity of the monad or the fold-point. Everything is packed into this infinitesimal summit. It's not the same as the Platonic concept which is pure and nothing-but-itself, or the Aristotelian concept with is a genera that requires specification. It's not an arbitrary symbolic representative of the world, but a whole allegorical story of how all this diversity unfolded from a single principle. In short, it's a theodicy, a creation or unfolding of the concept into a world.

Thus the fold gives us a completely different idea of what a unity can be, and how it is related to the multiple. The unity of the monad is already multiple since it includes the whole world that can be projected. And the images of the base already have a unity insofar as they can all be seamlessly folded back into the summit of the cone. As we saw at the outset, the material base is folded, and the soul is folded, and the two are folded together, each with a distinct though interlocking type of unity. It's this observation which finally brings us back to the explanation of the diagram above.

The one always being the unity of the multiple, in the objective sense, there must also be a multiplicity "of" the one and a unity "of" the multiple, this time in a subjective sense. Whence the existence of a cycle, "Omnis in unum," such that the one-multiple and multiple-one relations are completed by a one-one and multiple-multiple relation, as Michel Serres has shown. This square finds its solution in the distributive character of the one as an individual unity or Each, and in the collective character of the multiple as a composite unity, a crowd or a mass. It is the belonging [appartenance] and its reversal that show how the multiple belongs to a distributive unity, but also how a collective unity belongs to the multiple. (F, 174)

The top half of the diagram refers to the soul, the bottom floor to the body. The folds of the soul are the "multiplicity of the one", (the top solid arrow) the infinity of obscure micro-perceptions inside every monad that correspond to the shadows projected from all the other monads. The folds of organic matter are the subjective "unity of the multiple" (the bottom solid arrow,) the organs which compose unified organisms to infinity. But, as we saw in our discussion of belonging, these two sides are also folded together, intimately interlocking on an infinity of scales. So that the body which belongs to me in a unique one-to-one correspondence under the vinculum (left hand two-way dashed arrow) turns out to be composed of a mass of organs, which have a many-to-many correspondence to the crowd of monads that my monad dominates (right hand two-way dashed arrow). Folding and unfolding is the act that endlessly carries us around this cycle, which expands in horizontal breadth at the base and increases in spiritual height at the summit.